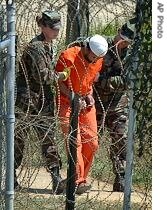

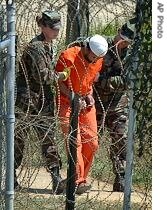

"While an international debate rages over the future of the American detention center at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, the military has quietly expanded another, less-visible prison in Afghanistan, where it now holds some 500 terror suspects in more primitive conditions, indefinitely and without charges." "While an international debate rages over the future of the American detention center at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, the military has quietly expanded another, less-visible prison in Afghanistan, where it now holds some 500 terror suspects in more primitive conditions, indefinitely and without charges."

That is the opening line of a front-page article in Sunday's New York Times detailing the US-run prison at Bagram Air Base, north of Kabul. The Times reports that some of the detainees at Bagram have been held for as long as two or three years. Unlike those at Guantanamo, they have no access to lawyers, no right to hear the allegations against them and only rudimentary reviews of their status as "enemy combatants." One Pentagon official told the Times the current average stay of prisoners at Bagram was 14.5 months.

The numbers of detainees at the base had risen from about 100 at the start of 2004 to as many as 600 at times last year. The paper says the increase is in part the result of a decision by the U.S. government to shut off the flow of detainees to Guantanamo Bay after the Supreme Court ruled that those prisoners had some basic due-process rights. The question of whether those same rights apply to detainees in Bagram has not been tested in court.

While Guantanamo offers carefully scripted tours for members of Congress and journalists, Bagram has operated in rigorous secrecy since it opened in 2002 It bars outside visitors except for the International Red Cross and refuses to make public the names of those held there. The prison may not be photographed, even from a distance.

Citing unnamed military officials and former detainees, the Times reports that prisoners at Bagram are held by the dozen in wire cages, sleep on the floor on foam mats and are often made to use plastic buckets for latrines. Before recent renovations, detainees rarely saw daylight except for brief visits to a small exercise yard. The U.S. military on Sunday defended Bagram air base saying detainees there are treated humanely and provided "the best possible living conditions."

But evidence of abuse of prisoners at Bagram has emerged over the years. In December 2002, two Afghan prisoners were found dead, hanging by their shackled wrists in isolation cells at the prison. An Army investigation showed they were treated harshly by interrogators, deprived of sleep for days, and struck so often in the legs by guards that a coroner compared the injuries to being run over by a bus. No one has been prosecuted for the deaths, though both were ruled homicides and the Army claims the men were beaten to death inside the jail.

We are joined on the line by Clive Stafford Smith, a British-born human rights lawyer who represents 40 detainees at Guantanamo Bay, many of whom passed through Bagram Air Base. He is legal director of the charity Reprieve We are also joined by Michael Ratner, president of the Center for Constitutional Rights.

Clive Stafford Smith, a British-born human rights lawyer who represents 40 detainees at Guantanamo Bay, many of whom passed through Bagram Air Base. He is legal director of the charity Reprieve.

Michael Ratner, president of the Center for Constitutional Rights.

AMY GOODMAN: We're joined on the phone right now from London by Clive Stafford Smith, a British-born human rights lawyer who represents 40 detainees at Guantanamo Bay, many of whom passed through the Bagram Air Base He is legal director of the charity, Reprieve. He joins us on the phone from London. Welcome to Democracy Now!

CLIVE STAFFORD SMITH: Good morning.

AMY GOODMAN: Itís good to have you with us. Can you tell us what you know of Bagram?

CLIVE STAFFORD SMITH: Yes, and, of course, a lot of it is laid out in the New York Times, but there are some things that are considerably worse than represented there. For example, there is an area of Bagram that is not open to the Red Cross, as one of our clients, Mamdou Habib said. The most frightening moment he had in Bagram was when the Red Cross came and he didnít get to see them. And thereís a cellar area in Bagram, a dark -- a place thatís kept perpetually dark, which is where a number of prisoners are kept away from the Red Cross itself. And, of course, if you think about being a prisoner in those circumstances, your natural assumption is if the military doesn't want the Red Cross to know you exist, then your fate is probably not going to be a very pleasant one, and naturally a number of those people have been moved off and rendered to other countries, where they have been abused. And some of them weíve caught up with again in Guantanamo, but many haven't. Theyíve disappeared.

AMY GOODMAN: We're also joined in our studio by Michael Ratner, President of the Center for Constitutional Rights. Does the Center represent people at Bagram?

MICHAEL RATNER: Well, like Clive, the Center has many of the similar clients who have been through Bagram on their way to Guantanamo. And Moazzam Begg is another one whose story has just come out, how he was taken to Bagram, beaten, etc., and then went to Guantanamo. We are in contact with people who have family members, who have people in Guantanamo, and as Clive said, a lot of this has been known for a couple Ė more than two or three years. I mean, the people who were hung and tortured and killed. The underground prison has been known, and whatís really incredibly frustrating Ė you feel like Sisyphus, rolling the stone up the hill, when you think about finally getting some rights for people and visits to Guantanamo, and then what happens is the administration really goes and continues its illegality in other prisons around the world. So what it really says is that, yes, the struggle is around one prison like Guantanamo, but we have to really root out completely what this administration is doing around the world.

AMY GOODMAN: Now, can you, though, explain? I mean, it sounds like the reason Bagram is growing is because of all of the international outcry around Guantanamo, but also Guantanamo's legal relationship with the United States on a U.S. air base in Cuba. Can you explain the legality of Afghanistan, where Bagram is and Guantanamo, these two detention camps?

MICHAEL RATNER: Well, both Clive and I were in the early case about Guantanamo, in which the U.S. tried to say Guantanamo was like Bagram, that there were no legal rights there. You couldn't go to court for people in Guantanamo. They had no constitutional rights, and the U.S. said it could do what it wanted to people at Guantanamo. We won a big case in the Supreme Court, the Rasul case in June of 2004, that opened the courts to people at Guantanamo and opened them so people like Clive and Center lawyers could go to Guantanamo.

Even with that, those set of rights, the administration, in the Graham-Levin Bill and the Detainee Treatment Act, is trying to eliminate even those rights we won in the Supreme Court. But as far as Bagram is concerned, the legal position of the administration is similar to what it was about Guantanamo. There are no legal rights, but they have the additional argument that they would make, that because itís not on a U.S. permanent military base like the one in Cuba, that thereís even fewer rights.

I don't think they're correct. I think that any person detained anywhere in the world has a right to go into a court, has a right to be visited by an attorney, but the administration's view is whatever Guantanamo rights are, the rights at Bagram are nil, absolutely none, and so what they did, according to the Times report, was a few months after we won the Rasul case, they said they stopped sending people to Guantanamo and started to send them to other places Ė Bagram is the one that we know the most about at this point Ė because the administration's view is that no court, no lawyer, no one, has any right to visit anyone in Guantanamo -- anyone in Bagram, and that nobody --and that the people at Bagram have no legal rights at all. An extraordinary statement in todayís world.

AMY GOODMAN: Clive Stafford Smith, your response, and also what is the role, if any, of Britain in Bagram?

CLIVE STAFFORD SMITH: Well, my response is that I think, as Michael and I and many others have said for a long time, Guantanamo is something of a distraction. That people -- if you think people have been badly treated in Guantanamo, you should see whatís happened to them in other places, and whatís of real concern, arising out of the New York Times article, is this: The Times mentioned one flight. It was actually September 19, 2004 where ten people were brought to Guantanamo. I represent a couple of those. Of those ten, all of them are extraordinary cases where people were taken and abused horribly in other places.

One of my clients is Binyam Mohammed. He was rendered to Morocco. Weíve got the flight logs. We know the very names of the soldiers who were on the flight, and he was taken there, and he was tortured for 18 months, a razor blade taken to his penis, for goodness sake, and now the U.S. military is putting him on trial in Guantanamo. Hassin bin Attash, a 17 year-old juvenile who was taken to Jordan and tortured there for 16 months. There is a series of these people.

Now, what that prompts is this question, that the people who have been most mistreated in Guantanamo were mistreated elsewhere, and then the administration took a very small number of them to Guantanamo, but the vast majority of them are either in Bagram or in these secret prisons around the world. And most recently, we heard of Poland. Weíve heard of Morocco. Weíve heard of various places.

What I'm afraid is the truth is that the most shocking abuses have yet to come to light, that these people are in Bagram and have yet to talk to anybody, and what the administration is doing is hiding these ghastly secrets. Now, the question is: What are they going to do about that? What are they going to do when it becomes necessary at some point for these prisoners to be given lawyers? Thereís a lot of horror stories, and the administration is just not going to want those horror stories to come out. So where are these prisoners going to be sent? Are they going to vanish forever?

And unfortunately, the U.S. administration has shown that it is willing to send people to Egypt, where they may disappear, to Morocco, where they get razor blades taken to them, and weíve got to find out the names of these people first, because the government won't tell us, and then weíve got to prevent them from being rendered to some country where they effectively die after a bit of torture. Iíll be glad to go on to the British part, but I know I have talked too much I donít want to rant on forever.

AMY GOODMAN: Clive Stafford Smith, I wanted to ask you about a piece that appeared in a paper in your country in the Guardian by Suzanne Goldenberg and James Meek. It says, "New evidence has emerged that U.S. forces in Afghanistan engaged in widespread Abu Ghraib-style abuse, taking trophy photographs of detainees and carrying out rape and sexual humiliation. Documents obtained by the Guardian contain evidence that such abuse took place in the main detention center at Bagram, near the capital, Kabul, as well at a smaller U.S. installation near the southern city of Kandahar. A thousand pages of evidence from U.S. Army investigations released to the ACLU after a long battle, made available to the Guardian."

And then inside, it says, "The latest allegations from Afghanistan fit a pattern of claims of brutal treatment made by former Guantanamo Bay prisoners and Afghans held by the U.S. In December, the U.S. said eight prisoners had died in custody in Afghanistan," and this is according to you, "A Palestinian says he was sodomized by American soldiers in Afghanistan. Another former prisoner of U.S. forces, a Jordanian, describes a form of torture which involved being hung in a cage from a rope for days. Hussein Abdelkader Youssef Mustafa, a Palestinian living in Jordan, told Clive Stafford Smith he was sodomized by U.S. soldiers during detention at Bagram in 2002. He said, ĎThey forcibly rammed a stick up my rectum Ė excruciatingly painful. Only when the pain became overwhelming did I think I would ever scream, but I could not stop screaming when this happened.í"

CLIVE STAFFORD SMITH: Yeah, you know, Hussein Mustafa, I met with him in Jordan, and he was an incredibly credible person. He is a dignified older gentleman, about now 50 years old, and he wanted to talk about what had happened to him, but he really didnít want to talk about that sexual stuff, and in the end, you know, I said to him, "Look, you donít have to, but itís very important if things happened, that the story get out, so they don't happen to other people," and in the end he did, and it was in front of half a dozen people who were just transfixed as he described how four soldiers took him, one on each shoulder, one bent down his head and then the fourth of them took this broomstick and shoved it up his rectum.

Now there was no one in that room -- and they were from a variety of places -- who didn't believe that what this man was saying was true, but I am afraid, Iíve got to tell you, that thatís far from the worst thatís happened When you talk about Bagram, when you talk about Kandahar, those arenít the worst places the U.S. has run in Afghanistan. The dark prison, sometimes called "Salt Pit," in Kabul itself, which is separate from Bagram, has been far worse than that, and I can tell you stories from there that just make your skin crawl.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, why don't you tell us something about this place?

CLIVE STAFFORD SMITH: Yeah, I'll tell you some of the ones, for example, that Binyam Mohammed told me. He was the man who had the razor blade taken to him. He was then taken, and again, we can prove it. Weíve got the flight logs. He was taken on January 25, 2004, to Kabul, where he was put in this dark prison for five months, and he was shackled. You just get this vision of the Middle Ages, where heís shackled on the wall with his hands up, so he can't quite sit down. Itís totally dark in that place.

When the U.S. says that people are being treated nicely in Bagram, youíve got to be kidding me. Itís the middle of winter, and they're freezing to death, and this man was in this cell, no heating, absolutely freezing, no clothing, except for his shorts, totally dark for 24 hours a day with this howling noise around him. They began with Eminem music, interestingly enough they played him Eminem music for 24 hours a day for 20 days. Seems to me Eminem ought to be suing them for royalties over that, but then it got worse and they started doing these screeching noises, and this is going on 24 hours a day, and in the mean time they would bring him out very briefly just to beat him, and this is to try to get this man to confess to stories that they now want him to repeat in military commissions in Guantanamo, and they want to say, "Oh, everything's nice now."

And what he went through, he said, was far worse than the physical torture, this psychological torture that some pervert was running in the dark prison in Kabul was worse to him, and he still suffers from it day in, day out, because of what it has done to his mind, and this is the Ė what we have to remember is there is someone out there who is thinking this stuff up and who is then saying that we need to do it, and this isnít some lowly guard who loses control and does something terrible thatís physical. I mean, thatís awful. But youíve got someone out there who is thinking through how weíre going to torture these people with this excruciating noise and these other things, and they're doing this very, very consciously, and the story has a long way before itís going to be out fully.

AMY GOODMAN: So, Michael Ratner, what oversight is there?

MICHAEL RATNER: Well, as Clive is saying, there isn't, and I think, you know weíre putting this huge effort into closing down Guantanamo, which is crucial, obviously, to do. It will be a major victory, but what weíre running is these so-called "black sites," torture chambers all around the world, and there isnít any oversight. Our Congress is just sitting on its hands, not doing anything. The most they ask is they say, "Give us a report on black sites." Even that isnít getting through. We have nothing.

This country is running torture chambers around the world right now, and Clive's stories, our clientsí stories, are incredibly dramatic, and his point about the psychological torture is crucial. Itís what Clive is saying, people have thought about this, but this is something that has been U.S. policy for 40 years of how to really deal with people, not just physically, but with psychological torture, and one of your former guests, I think Al McCoy, had this on in A Question of Torture, saying, this is what really affects people. Physically, yes, hurts them, but the psychological marks of torture, and when you see the pictures from Bagram to Guantanamo, you know that this is stuff that is not just chance or random. This is going by the book.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to talk about this article in the New Yorker that Jane Mayer had written about Colonel Louie Morgan Banks, a senior Army psychologist who played a significant advisory role in interrogations at Guantanamo Bay. Asked to provide details of his consulting work, he said, quote, "I just don't remember any particular cases. I just consulted generally on what approaches to take. It was about what human behavior in captivity is like." Banks has a Ph.D. in psychology from the University of Southern Mississippi. A biographical statement for an American Psychological Association Task Force on Psychological Ethics and National Security, which Banks serves on, mentions that he, quote, "provides technical support and consultation to all Army psychologists providing interrogation support." It also notes that starting in November of 2001, Banks was detailed to Afghanistan where he spent four months at Bagram Air Field, quote, "supporting combat operations against al-Qaeda and Taliban fighters."

MICHAEL RATNER: Well, whatís remarkable about Banks is he also consulted on Guantanamo. So here you have this guy who is a psychologist, consulting really on how to break people through psychological -- psychological torture is what I would call it, and then he goes from Guantanamo to Bagram. This is not chance. This is not a few bad apples. This is high-level military people working with our military, our C.I.A., in how to break people through torture.

CLIVE STAFFORD SMITH: When you're talking "break people," and I think thatís a very important word. You know, people bang on about whether itís torture or whether itís coercion. Well our highest officials have said that the purpose of all of this is to, quote, "break" somebody, and we get people to confess to stuff thatís absolute drivel. You take, for example, Binyam Mohammed, again. You have a razor blade taken to you, you have the psychological stuff, youíre going to say anything.

They got Binyam Mohammed to confess that he had dinner with Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, Ramsey bin al-Shaid, Abu Zubaydah, Sheikh al-Libbi, and Jose Padilla all together on April 3, 2002, in Pakistan. Well, you know, quite apart from anything else, two of them, Abu Zubaydah and Sheikh al-Libbi were in U.S. custody at the time when he confessed to that and at the time that he was meant to be having dinner, and you know, this is a guy that didnít speak Arabic who was meant to be hobnobbing with half of al-Qaeda. You get this total drivel out of this breaking of people, and yet, for some reason, the people who are designing Guantanamo think we should carry on breaking them, as did the Spanish Inquisition. Itís very odd.

MICHAEL RATNER: Thatís correct. I mean, itís Ė they break them; they get drivel; they get false stories, and so whatís going on? Whatís going on, I think, in part, is an attempt to terrorize people, terrorize the Muslim world and say, "You come into U.S. hands, and we will terrorize you." And thatís what theyíre doing.

CLIVE STAFFORD SMITH: Donít you think though, Michael Ė I tell you, I think thereís a slightly bigger danger here, which is the people who are doing this abuse believe the stuff they get. This is whatís frightening to me, that we end up making decisions based on this nonsense.

MICHAEL RATNER: You know, itís true. They do believe it. I think, when you talk to your clients or we talk to ours, the people who are interrogating them actually believe what they're telling them, even though itís utterly and complete drivel.

AMY GOODMAN: Weíre going to have to leave it there. Joining us next is Maher Arar. He is a Canadian citizen who was -- well, the U.S. government calls it "extraordinary rendition," others call it "kidnapped" -- when he was transiting through Kennedy Airport from a family vacation to Canada and sent to Syria, was tortured there and held for almost a year. We have been speaking with Clive Stafford Smith, a British human rights lawyer. Michael Ratner will stay with us, President of the Center for Constitutional Rights.

- Click Here for Guantanamo Bay Information

|

The Associated Press yesterday sued the Defense Department for the release of records identifying all past and current detainees at the US-run prison camp in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. The AP's suit was filed after the Pentagon failed to respond to a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit filed by the AP in January. Last month, the military was ordered to turn over uncensored copies of transcripts from hearings for detainees held at Guantanamo. The transcripts were released, however they were censored, and names and other key details were blacked out. The Associated Press yesterday sued the Defense Department for the release of records identifying all past and current detainees at the US-run prison camp in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. The AP's suit was filed after the Pentagon failed to respond to a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit filed by the AP in January. Last month, the military was ordered to turn over uncensored copies of transcripts from hearings for detainees held at Guantanamo. The transcripts were released, however they were censored, and names and other key details were blacked out.

As international calls grow for the closure of the US-run prison camp at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, today we bring you a voice rarely heard in the US media, that of a former Guantanamo prisoner. In a Democracy Now broadcast exclusive, today we hear Moazzam Begg in his own words.

Moazzam is a British citizen born and raised in Birmingham. The story of his ordeal begins in mid-2001 when he moved to Afghanistan with his wife and three young children to work as an aid worker in education and water projects. After September 11th and the subsequent U.S. bombing of Afghanistan, he relocated to Pakistan.

In February 2002, Moazzam was seized by the CIA in Islamabad. No reasons were given for his arrest. He was hooded, shackled and cuffed and flown to the U.S. detention facility at Kandahar, then to Bagram airbase where he was held for approximately a year before being transferred to Guantanamo Bay. The U.S. government labeled him an "enemy combatant." He was never charged with a crime.

In all, Moazzam spent three years in prison, much of it in solitary confinement. He was subjected to over three hundred interrogations as well as death threats and torture. At Bagram, he witnessed the killing of two fellow detainees.

In January 2005, he was finally released from Guantanamo along with three other British citizens. He received no apology or compensation for his imprisonment.

Moazzam Begg has written a book about his experience that has just been published in the UK titled "Enemy Combatant: A British Muslim's Journey to Guantanamo and Back." It is the first book known to be published by a former Guantanamo Bay prisoner. The book is co-written by Victoria Brittain, a former associate foreign editor of the Guardian newspaper.

Last week, Victoria Brittain and Moazzam Begg held a public conversation and Q&A at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in central London. Democracy Now was there to cover the story. In this U.S. national broadcast exclusive, we bring you Moazzam's first comments to air in this country since he wrote his book. At the event, I had the chance to ask Moazzam about the abuse he suffered while in prison.

Moazzam Begg, former Guantanamo detainee and author of the book, "Enemy Combatant: A British Muslim's Journey to Guantanamo and Back"

AMY GOODMAN: Last week, Victoria Brittain and Moazzam Begg held a public conversation at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in Central London. Democracy Now! was there to cover the story. In this national broadcast exclusive, we bring you Moazzamís first comments to air in this country since he wrote his book. After he and Victoria Brittain spoke, I had a chance to ask Moazzam about the abuse he suffered while he was in prison.

AMY GOODMAN: Moazzam, though you are almost synonymous with Guantanamo, when people think about it, in your book you describe being tortured at Bagram. And I was wondering if you could talk about what happened to you there, who tortured and interrogated you, and if you saw other people or knew of other people at Bagram who were killed or abused.

MOAZZAM BEGG: Yeah. I think itís important also to note that when we are talking about Guantanamo Bay, in a sense, or in fact, itís not as bad as Bagram at all. People know about Guantanamo Bay, because itís in the news every day. You hear about it. You think itís this terrible place, and it is, because of the absence of the law. But whatís worst than Guantanamo Bay are places like these black holes of detention, where you don't know whatís going on, where there is no access to media, where the media doesn't know whatís going on, and neither does anybody else, including the relatives and so forth. There is no communication. And it is a place thatís Ė itís a military base, but the C.I.A. has complete and utter control of what takes place there. And no wonder in places like Bagram people are killed, and no wonder in Guantanamo Bay we haven't heard of any deaths yet, because in places like Bagram, they can try and justify themselves by the proximity, as they call it, towards the war zone.

While I was held in Bagram, it was probably one of the hardest periods of the whole of the incarceration. One particular month in May, I was subjected to some extremely harsh interrogation techniques, which included being -- or having my hands tied behind my back to my legs like an animal, as they call in America "hogtied," with a hood placed over my head so I was in a suffocating position, kicked and beaten and sworn at and spat at, left to rot in this position for hours and hours on end and taken again into interrogation, and this lasted over a period of over a month.

That wasn't the worst of it, of course. The worst of it, for me, was the psychological part, because all of this time I had no communication with my family at all. I didn't know what happened to my wife or my children. For all I knew, they could have done terrible things to them. And that was the biggest fear.

And I met the International Committee of the Red Cross, and they allowed me to write letters, but, of course, all of these letters had to be passed through the U.S. military censorship, and they must have read all of the letters, and in them I expressed my deep anguish about the state of asking where my wife was to my parents. In one of the interrogations, I remember quite clearly, they had this -- I heard the sounds of a woman screaming. And at the back of my mind, I thought, no, it can't be what I truly think it is. And as the screaming got worse and worse and the shouting to this woman got worse, my heart rate went up, and I started imagining the unimaginable. And certainly they were playing on this. It was, I believe, to this day it probably written on my file: if you want to get to this guy, do it through his family. And so, that was definitely one of the hardest parts. Many detainees, even, in fact, afterwards, when I was removed from that isolation unit, said that, you know, we were praying to God that itís not your wife. Well, thankfully, it wasn't.

And the worst situation, I think, that I saw there was the deaths of the detainees. I mean, you can see -- you can deal with your own abuse to some degree. What you can't do is to see somebody elseís and then sit by and let it happen, and yet I was in such a impotent position that I saw a person who had been chained with his hands above his head like this, which is what theyíd often do, which would often happen to me if I was just talking to the person next door to me, which was deemed punishable. This person was left suspended like this for hours, and eventually guards came and they beat him, dragged him upstairs, and we never saw or heard of him again.

A year-and-a-half later, internal investigators from the military came and asked me if I would look at a picture. They showed me a picture, and it was a man's body, and they said that he had been killed, could I describe any of the details that I had saw in Bagram at that time, and I described to them what I saw. And then they brought photographs of the people that they said were responsible Ė could be responsible from the military units, the M.P.s, and I pointed out to the people who I believed had done it. And then, ironically, this was a time when I was in solitary confinement, also worried about facing a possible military commission by President Bush's order, they said, "Would you be ready to stand up as a witness in a trial against these perpetrators?" That was so ironic.

AMY GOODMAN: Who did it to you?

MOAZZAM BEGG: Oh, the interrogators at the time? Yes, it was a whole group of them. There were C.I.A., F.B.I., and Military Intelligence. Those were at least the three groups that were there during that interrogation.

AMY GOODMAN: Moazzam, you talked about one of the men who was killed at Bagram, and you described the guard at Guantanamo who talked about killing another. How did he kill that person?

MOAZZAM BEGG: What had happened, I think the detainee's number was 284, as I recall. This was said to be an escape attempt at the backs of the cells in Guantanamo -- in Bagram. They were all common [inaudible]. There was about seven or eight people in each cell. At the back of the cell was this barrel that they had cut in half, which was, you know, the toilet. That was surrounded by some barbed wire. He apparently had pushed the barbed wire through, pushed the barrel and tried to escape. The guards caught him, jumped on him and, in essence, threw Thai boxing-style strikes at him, as this guy told me. And I saw them dragging his body across the cell where I was held, in cell 6, into the medical room, right in front where we were. At that point, I wasn't sure whether he was dead, but he looked completely battered and bruised, and all the dust that was on him. A while after that, after all the medics and the officers were running around this area, his body was carried out on a stretcher with the sheet covering his head.

AMY GOODMAN: And the sexual abuse at Guantanamo and at Bagram?

MOAZZAM BEGG: UmmÖ

VICTORIA BRITTAIN: I donít think you need to go into that.

MOAZZAM BEGG: I would rather just not answer that here.

VICTORIA BRITTAIN: I think weíll leave that.

AMY GOODMAN: Moazzam Begg, speaking last week in London at the Institute of Contemporary Art, just after the British release of his book, Enemy Combatant. Itís coming to this country in the fall. These are his first national broadcast comments in this country. Imprisoned at Bagram Air Base, and then Guantan amo for over three years. When we come back we talk to his co-writer of the book, Victoria Brittain, the former Associate Editor of the Guardian, and we will also speak with his attorney, Gareth Peirce.

- Click Here for Guantanamo Bay Information

|

"While an international debate rages over the future of the American detention center at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, the military has quietly expanded another, less-visible prison in Afghanistan, where it now holds some 500 terror suspects in more primitive conditions, indefinitely and without charges."

"While an international debate rages over the future of the American detention center at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, the military has quietly expanded another, less-visible prison in Afghanistan, where it now holds some 500 terror suspects in more primitive conditions, indefinitely and without charges."

The Associated Press yesterday sued the Defense Department for the release of records identifying all past and current detainees at the US-run prison camp in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. The AP's suit was filed after the Pentagon failed to respond to a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit filed by the AP in January. Last month, the military was ordered to turn over uncensored copies of transcripts from hearings for detainees held at Guantanamo. The transcripts were released, however they were censored, and names and other key details were blacked out.

The Associated Press yesterday sued the Defense Department for the release of records identifying all past and current detainees at the US-run prison camp in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. The AP's suit was filed after the Pentagon failed to respond to a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit filed by the AP in January. Last month, the military was ordered to turn over uncensored copies of transcripts from hearings for detainees held at Guantanamo. The transcripts were released, however they were censored, and names and other key details were blacked out.