|

02/01/2006

As their day of judgment looms, the Bali Nine are finally finding something to agree on - that God moves in mysterious ways. Paul Toohey reports.

Andrew Chan is talkative, which is odd. He’s never said anything before to the press, let alone to Indonesian police investigators or his own lawyers. He’s accused of being – along with Myuran Sukumaran – chief co-conspirator of the Bali Nine heroin operation. On this day, Chan’s waiting to attend his trial in a cell at the back of Denpasar District Court. In a few days, he will learn that the Indonesians want him shot for what he has done. Chan is in a weird state of mind. Pressing against the bars, I ask him if he’d like to talk. Andrew Chan is talkative, which is odd. He’s never said anything before to the press, let alone to Indonesian police investigators or his own lawyers. He’s accused of being – along with Myuran Sukumaran – chief co-conspirator of the Bali Nine heroin operation. On this day, Chan’s waiting to attend his trial in a cell at the back of Denpasar District Court. In a few days, he will learn that the Indonesians want him shot for what he has done. Chan is in a weird state of mind. Pressing against the bars, I ask him if he’d like to talk.

“What’s to talk about?” he says.

Your life.

“Huh?”

Are you worried?

“What’s the point in stressing myself out? I’m not worried. I’ve put my life in the hands of God.”

I would have thought you had put it in the hands of lawyers.

“Lawyers? I don’t worry about them.”

Why not? A good lawyer can save you, I say. But I’m thinking of Australia, where lawyers are able to get into a jury’s soul, to play with them and to cast just enough doubt. Indonesian trials do not run to juries.

Chan has done nothing to save himself. He’s given no excuses, no mitigation. There’s been no suggestion he was a desperate junkie, no stories about needing money to save a dying mother back home. Chan first came to the attention of Indonesian National Police courtesy of a letter sent by the Australian Federal Police on April 8, 2005, nine days before he was arrested. The letter advised police that Chan and friends were likely to buy heroin in Bali and bring it back to Australia. The AFP advised the INP to take whatever action they thought necessary with the group. Chan has done nothing to save himself. He’s given no excuses, no mitigation. There’s been no suggestion he was a desperate junkie, no stories about needing money to save a dying mother back home. Chan first came to the attention of Indonesian National Police courtesy of a letter sent by the Australian Federal Police on April 8, 2005, nine days before he was arrested. The letter advised police that Chan and friends were likely to buy heroin in Bali and bring it back to Australia. The AFP advised the INP to take whatever action they thought necessary with the group.

The INP did not gather hard evidence against Chan. While they followed Chan, they claim they missed the moment when he bought the heroin in Bali. There is some grainy surveillance footage of Chan meeting some of the nine in Bali, but the talks were not recorded. What did Chan in was that the four mules turned on him and Myuran Sukumaran, testifying that they were witless slaves, forced to do their pitiless masters’ bidding.

Chan’s right. His lawyers can’t save him. But he talks as though he now dwells not in the realm of men, but in a place where nothing of this Earth can possibly matter.

“God is the only thing I’m concentrating on,” he says. “Why should I do anything else?” Can God look after you in prison? “With the Holy Spirit, mate, with the Holy Spirit within you, you can do anything.”

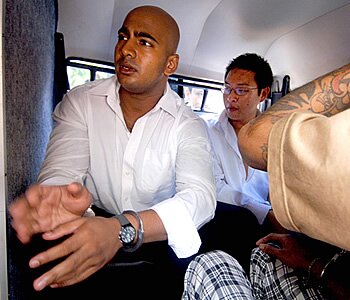

Chan, who has been presented to the public as the Godfather, suddenly doesn’t look so dangerous. He looks a little older than his 22 years, perhaps because of the spectacles he wears. He is sharing the courthouse cell with the youngest member of the nine, Scott Rush, who turned 20 in Kerobokan, and nine or 10 Indonesians. The Australians are dressed in long-sleeved white shirts and black trousers and look more like fresh young door-knocking Mormons than heroin conspirators.

While Rush is relaxed, Chan’s mind is elsewhere. He can’t keep still, screws up his face, doesn’t seem to want to answer questions but cannot drag himself away to go and sit in the darkest corner of the cell, away from prying eyes, as he has done on his previous court visits. He appears to be either out of it, on something, or borderline mental breakdown. Or perhaps he’s very scared and trying not to show it.

Why didn’t you cooperate with the court? Why not admit what you did and ask for mercy? “No one cares,” Chan says. “No one cares except for God. Let him worry.” The Bible will get him through. “I find a new verse every night to dwell on.” At the moment, he says, he’s reading the Old Testament’s Prophecy of Habacuc, a very obscure passage. I get the feeling I’ve heard this before – not about Habacuc, as such, but all this Bible bashing that’s coming out of Kerobokan. Schapelle Corby’s into it; so are most of the nine. I can hear Scott Rush talking to one of my colleagues, just a metre away. He is also giving God a workout.

Chan cites Chapter 2, verse three: “Just read it, man.” Later, looking through the atmospheric ramblings of Habacuc, lesser prophet, the message doesn’t seem to fit with Chan’s predicament. Habacuc predicts the terrible Chaldeans will come on horses lighter than leopards and swifter than evening wolves to destroy Jerusalem, because of the people’s wickedness; but thereafter, ruin will come to the Chaldeans and the Jewish people will rise again with the coming of Christ. Verse three advises that while the vision is coming we may have to wait for it. The question is whether Chan has that much time.

Christine Rush, mother of Scott, delivers McDonald’s cheeseburgers to Rush and Chan. Now there are TV cameras pointing into the gloomy cell and Chan is still unable to pull himself away. He rips into the cheeseburger with his teeth, holds it up and says, to the world: “Want to sponsor me, Maccas?”

Matthew Norman’s father, Michael, appearing as a character witness in his son’s trial, is struggling to follow questions. It’s not that his hearing aid is faulty, nor is it the traffic blaring right outside the courtroom window. It’s that the translator’s strong point isn’t her English. The translator finally gets the question across: what does Mr Norman hope for his son? The gentleman has heard what Michael has told him outside this courtroom and he believes his boy. Or wants to believe him. “My hope? I hope Matthew can come home, because he’s got nothing to do with this.”

The prosecutor, Olopan Nainggolan, a big man in black robes, leans back in his chair and rocks with laughter. He looks towards the judges, points towards Mr Norman as if to say: “Get a load of this guy.” One of the judges laughs along. Mr Norman smiles, failing to understand the joke but desperately trying to emanate a bit of confused goodwill in the hope it will help Matthew.

A few metres away, Matthew, hangdog and skinny, is bunched up with his co-accused, Tan Duc Thanh Nguyen, and Si Yi Chen. The three are sharing two chairs and there is one slow ceiling fan for the whole court room. The cables running along the floor do not lead to court-recording equipment because the trial is not being recorded. The leads are for amplification, but the system is barely functioning. The judges do not have court transcripts to study in order to arrive at their decisions. They just remember the key points and judge accordingly.

Chen’s father, Edward, says his only son was born in China. The family came to Australia when Si Yi was a boy. Mr Chen is not in the same state of denial as other parents. “I hope that for what he has done,” he tells the judges, “the court doesn’t punish him too hard.” Nguyen’s sister gives evidence, saying her brother is “a good boy” who never had any problems with drugs and would every week give half of his income to his family. Life, she says, is harder for the family now her brother is gone.

The interpreter is still struggling. It seems an unnecessary burden that these accused, facing such serious charges, cannot get a proper translator. The Bali Nine lawyers have dragged up a respected but ancient legal professor to explain import-export drug law to the judges. After giving evidence, he shakes hands with the judges, the prosecution and the defence and staggers slowly out of court. It’s all about appearances, not substance.

Over in the other courtroom, Michele Stephens, mother of accused mule Martin, tells how when she first heard her son had been arrested, the day after the bust, she didn’t believe it. Martin didn’t even have a passport. He’d told her he’d gone to Darwin on a furniture removal job. But then he had told her what had really happened: Andrew Chan, one of the accused ringleaders, had told Martin he’d kill his family if he didn’t do it. And so, by attempting to shift heroin into Australia, he’d potentially sacrificed his own life to save hers. Mrs Stephens told the court she believed her son, fully. She says she would not be here if she doubted him.

There, on the floor of the courtroom, is the evidence. The eight-plus kilos of heroin, and all the strapping and bandages that were said to have been used. No one’s guarding it but, then, who’d want it? Martin Stephens tells the court: “I’d just like to say when I came over to Bali I honestly did not know what I was here for.”

It’s funny, that. He came to Bali because if he didn’t, his family would be killed. Yet he didn’t know what he was here for. His gold crucifix hangs visibly, if not deliberately, outside his shirt.

Everyone’s turning to God. Australian Federal Police commissioner Mick Keelty says officers involved in Operation Midship, which saw the AFP hand over the nine young Australian heroin mules and organisers to Indonesian police, at one point developed such feelings of self-doubt about their part in selling out the nine that Keelty had to call a chaplain in. The cause of all this soul--searching, said Keelty, was because criticism of the AFP had become “so strong”.

It makes sense that Keelty blames critics – presumably, he means media – for this. Otherwise he’d have to reckon with the possibility that his officers’ angst was purely autonomous; that their respective consciences were in turmoil over the enormity of what they had done. Now that Indonesian prosecutors have called for death for two of the nine, and life or 20-year sentences for the remaining seven, how will the AFP rationalise this? Is it a good result? How can it be? The money the Australians brought to Bali to buy the drugs disappeared with the supplier after the INP bungled the whole operation and missed the buy. Or so we are told. Those who dealt the wholesale heroin have not been arrested. The trail seems to have gone cold.

When Chan and Sukumaran are shot, will that be a step forward in Australia’s war on drugs? One AFP staffer told The Bulletin it was “difficult to swallow” the line that the AFP “purposely sacrificed” these people to Indonesia. It was ludicrous and insulting.

Indeed, no one is suggesting AFP officers will rejoice in the executions. But when it comes to the likely deaths of Sukumaran and Chan, a chaplain may not have the right medicine to address the nauseating reality the AFP must face: that the sell-out of the nine Australians to a foreign country will go down as one of their darkest deeds. It is difficult to see who has benefited. It is certainly not Indonesia.

As Keelty rallies his troops, the parents of the Bali Nine – none of them rich, some retired – have been visiting financial planners to work out how to set aside enough from their savings, or to redraw on mortgages, so their jailed kids can live in moderate comfort inside Bali’s Kerobokan prison, and so that the parents can continue to fly regularly to Bali to visit them. Wills are being redrawn so their children will not be forgotten should the parents die. The nine are once again as babies, entirely dependent on their parents.

The parents of three of the mules agree to meet The Bulletin for their first formal sit-down interview about what has become of their lives, and how their children are coping. Part of the condition of that interview is that nothing negative be written about their children. It seems like a good idea, to cut such a deal; later it seems ridiculous.

The way it appears to have worked is that Sukumaran was the overall leader. He had two lieutenants, being Chan and Tan Duc Thanh Nguyen – although Chan was more senior than Nguyen.

Nguyen recruited Rush and Michael Czugaj in Brisbane. Two other mules, Renae Lawrence and Martin Stephens, both of whom worked with Chan at a catering firm in Sydney, were simultaneously recruited.

Rush’s lawyer, Robert Khuana, outlined a scenario in which Rush and Czugaj believed they were coming to Bali for an all-expenses holiday paid for by strangers. Khuana says it wasn’t until just hours before they were to fly home to Australia, that Chan and Sukumaran revealed to them, under threat of death, the reason for all this generosity. It is curious, given Rush’s line that Chan is a key person responsible for his likely life imprisonment, that they can stand together in a courthouse cell with their arms around each other. That Bible, with its messages of forgiveness, must be powerful stuff.

Lawrence’s and Stephens’ story is slightly different, in that they were brought to Bali under the supposed threat of death for themselves or their families. It is agreed that Chan, Sukumaran and Nguyen kept the two sets of mules entirely apart from each other when they were in Bali. They never met. But each pair was filmed separately meeting Chan, Sukumaran and Nguyen. As for Matthew Norman and Si Yi Chen, it seems certain they were to fly home later, once the group had sourced more heroin. And Norman was clearly involved more deeply than just being a simple mule.

According to Lawrence’s police statement, Chan and Sukumaran ordered her and Stephens to shift hotels to room 124 at the Adhi Dharma, in Kuta Beach, on the afternoon of the fateful flight home. At 5pm, Norman came to room 124 carrying a backpack. He said, according to Lawrence: “I feel rich carrying this bag.” He put it under a table and said: “Don’t touch it.” Shortly after, Chan and Sukumaran came in with more bags. The two put on gloves as the mules undressed. Both were strapped up, heroin packages attached around legs and chests. Then they were off to the airport.

One thing Stephens said in court, which had a ring of truth, was that by the time he had dressed up in drugs and oversize clothes, he could hardly move. “I don’t know how they thought we would get away with it.”

Rush and Czugaj ask to be believed that people take strangers overseas for holidays. Lawrence and Stephens ask the court to accept they had no alternative but to become couriers. It is difficult to swallow their stories. As such, it would not be sporting to use any of the information obtained from the parents during that interview. All I will report from that meeting is something one of the parents said: that flying home from Bali, leaving her child in Kerobokan, is the hardest thing she has ever had to do.

The court plans a verdict by February 14. Only then will the Bali Nine know whether the judges accept the recommendations of prosecutors – death for Chan and Sukumaran, life for Nguyen, Stephens, Chen, Norman, Czugaj and Rush, and 20 years for Lawrence, looked upon favourably for detailed statements naming Chan and Sukumaran as ringleaders.

Bali 9 Case Information

|