|

By , Stars and Stripes

Since he was accused of raping an Okinawan woman June 29, Air Force Staff Sgt. Timothy B. Woodland has glimpsed a side of Japanese society criticized by Japan bar associations and human- rights groups.

The criminal justice system is riddled with alleged human- rights abuses, and the case of Woodland, who goes on trial Tuesday, draws attention to these issues, said Seigo Fujiwara, vice president of the Japan Federation of Bar Associations.

It reveals the problems again that the bar association has been pointing out: in some areas, the Japanese [criminal justice] system is far behind international standards, he said.

On paper, Japans Constitution and criminal procedure codes protect the rights of criminal suspects and prisoners. But, in reality, thats not always the case, said Hideki Morihara, campaign coordinator for the Japan chapter of Amnesty International.

Allegations of human-rights violations documented by JFBA, a group of 18,224 defense lawyers, range from the subtle to horrific. A toilet in a prison cell floor that can be flushed only by guards. A prisoner with hands bound in back by leather handcuffs, unable to clean himself after defecation. A suspect who would not confess jabbed in the stomach, kicked in the thigh, and told, You are lower than an animal, by police interrogators.

Theres a huge gap between what is stated in law, and practice and implementation, Morihara said.

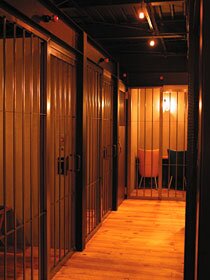

Substitute prisons

Bar associations and human- rights groups in Japan are critical of daiyo-kangoku what is known as the substitute prison system. A substitute prison is a police station cell where suspects may be detained, prior to indictment, up to 23 days after arrest.

JFBA calls these substitute prisons one of the most peculiar detention systems in the modern world.

Lengthy interrogations, that sometimes turn violent, are a product of the substitute prison system, JFBA maintains.

Investigators often questioned Woodland from 10 a.m. to 11 p.m, with a break for lunch, while he was detained at the police station, said Annette Eddie-Callagain, Woodlands American attorney in Okinawa.

Interrogations are not regulated by law and can last 12 to 16 hours a day, Morihara said. Defense lawyers cannot be present, and interrogations are not usually recorded.

In a written response to a Stripes inquiry, Japan Ministry of Justice officials said measures to protect suspects rights during interrogation are considered. These include meal and break times, and a limit of 23 days in pre-indictment detention; torture and cruel punishments are absolutely forbidden, and suspects are notified they have the right to remain silent.

Hostage justice

Japans Code of Criminal Procedure provides for bail as a statutory right, but Japan bar association members say this a hollow promise.

While a suspect in a Western country usually faces trial while released on bail, more than 80 percent of suspects in Japan face trial while still in custody, they said. Under these circumstances, the so-called right to bail in Japan is far from being a right.

Morihara said if a defendant denies a charge, its impossible to get bail. The suspects silence or denial is seen as a tendency to destroy evidence or talk to witnesses if released. In effect, it becomes a tool for coercing confessions.

We call this system hostage justice, JFBA wrote in a 1998 report to a United Nations Human Rights Committee.

Criminal laws also provide that a suspect may be detained if there is sufficient reason to believe he may destroy evidence.

In 99.4 percent of cases, the court grants the prosecutors request to detainment before indictment.

After indictment, roughly one in five suspects is released on bail, according to Amnesty International figures.

Prosecutors, Government of Japan officials said, screen a case carefully before indictment

A court-appointed attorney is not approved until after indictment, and suspects must rely on their own resources to hire an attorney before theyre formally charged. Local bar associations may provide detainees with a free counseling session prior to indictment.

Defense lawyers dont come into play until its too late, said Eddie-Callagain.

Woodland has two Japanese lawyers, as well as Eddie-Callagain. Last month the Naha District Court in Okinawa denied Woodland bail.

Eddie-Callagain believes one reason her clients request was turned down is because he has not confessed.

Confessions arent sought as much for evidence as an expression of moral repentance, which investigators see as necessary for rehabilitation and reintegration into society, JFBA said.

Japans Constitution does not compel criminal suspects to make a self-incriminating confession, yet about 90 percent of all criminal cases going to trial include confessions, says a 1998 U.S. State Department report on human rights in Japan.

Strict prison life

Woodlands U.S.-Japan Security of Forces Agreement status may protect Woodland from some conditions forced on Japanese prisoners.

They do have much better treatment, said Koichi Sekizawa of SOFA members in Japanese prisons. Sekizawa is a legal adviser in the staff judge advocates office of Commander Fleet Activities, Yokosuka Naval Base.

There are 11 U.S. servicemembers serving time in Japanese prison, all at Yokosuka Prison in Kurihama outside of Tokyo. Four are former Marines, five are Navy, and two Air Force. One woman, a dependent, is at Tochigi prison northwest of Tokyo.

Servicemembers, like other foreigners and Japanese prisoners, work while in jail. The labor shops include printing name cards for contractors and cleaning rugs, Sekizawa said.

But they eat better. According to information from the Ministry of Justice, supplied to JFBA in 1998, the U.S. military provides food for its servicemembers at Yokosuka Prison. The food is cooked in the prison.

U.S. servicemembers live in single rooms, while Japanese prisoners at Yokosuka Prison live alone or with other inmates.

All the prisoners Japanese, U.S. servicemembers and foreigners should be treated equally in prisons, JFBAs Fujiwara said.

Reform coming?

Japans criminal justice system is not completely flawed, Morihara said, but reform is necessary.

The governments Judicial Reform Council is proposing what it calls bold reform of the present judicial system, but Morihara is skeptical it will lead to more rights for suspects and prisoners in Japan.

Naoko Sekioka contributed to this report.

|