This is an undated photo of the death chamber at San Quentin State Prison in San Quentin, Calif. Faced with grim testimony of poorly trained executioners operating in cramped, dimly lit quarters, U.S. District Judge Jeremy Fogel |

By RON WORD, Associated Press Writer - Sat Dec 16 2006

JACKSONVILLE, Fla. - Death penalty foes have warned for years of the possibility that an inmate being executed by lethal injection could remain conscious, experiencing severe pain as he slowly dies. Angel Nieves Diaz, a career criminal executed for killing a Miami topless bar manager 27 years ago, was given a rare second dose of deadly chemicals as he took more than twice the usual time to succumb. Needles that were supposed to inject drugs into the 55-year-old man's veins were instead pushed all the way through the blood vessels into surrounding soft tissue. A medical examiner said he had chemical burns on both arms.

"It really sounds like he was tortured to death," said Jonathan Groner, associate professor of surgery at the Ohio State Medical School, a surgeon who opposes the death penalty and writes frequently about lethal injection. "My impression is that it would cause an extreme amount of pain."

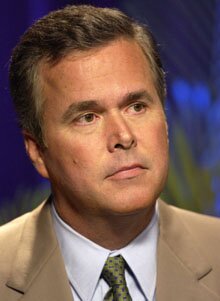

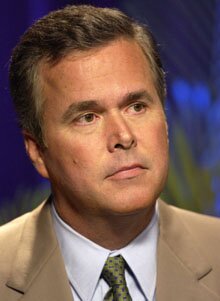

The error in Diaz's execution led Gov. Jeb Bush to suspend all executions Friday. Separately, a federal judge extended a moratorium on executions in California, declaring that its method of lethal injection violates the constitutional ban on cruel and unusual punishment.

They were just the latest challenges to lethal injection the preferred execution method in 37 states. Missouri's injection method, similar to California's, was declared unconstitutional last month by a federal judge. The U.S. Supreme Court has upheld executions despite the pain they might cause, but has left unsettled the issue of whether the pain is unconstitutionally excessive.

Diaz was given three drugs: to deaden pain, paralyze the body and cause a fatal heart attack. A study published last year in the British medical journal The Lancet concluded that the painkiller, sodium pentothal, could wear off before inmates die, subjecting them to excruciating pain when the potassium chloride causes a heart attack.

That study has been cited in unsuccessful appeals for death row inmates, who have claimed any pain experienced during lethal injection violates the cruel and unusual standard.

Dr. Nik Gravenstein, professor and chairman of anesthesiology at the University of Florida, said it is impossible to say how much pain the chemicals produce since inmates can't be interviewed while being executed, but he said patients given lower levels of the same chemicals for various treatments "describe this as being painful."

Dr. William Hamilton, the Gainesville medical examiner who performed the autopsy on Diaz, refused to say if Diaz died painfully until the autopsy is complete.

Florida Corrections Secretary James McDonough said the execution team did not see any swelling of Diaz's arms that would have indicated that the chemicals were going into tissues and not his veins.

McDonough also said reports that he received indicated Diaz had fallen asleep and was snoring.

However, witnesses reported Diaz was moving as long as 24 minutes after the first injection, including grimacing, blinking, licking his lips, blowing and attempting to mouth words.

It took 34 minutes for Diaz to die. Executions by lethal injection normally take about 15 minutes, with the inmate unconscious and motionless within three to five minutes.

Gravenstein said it can be difficult to get IV needles in their proper place. In a hospital setting, the average is 1.6 tries to successfully place an IV.

"The whole process has a lot of opportunity not to go as intended," he said.

He said someone should have realized what was happening.

"To have given somebody many times what is necessary and then to give them many more times again, it doesn't pass what one might call the 'red face test.' It just doesn't make sense. You have to be suspicious that something's not right," Gravenstein said.

Dr. Philip Lumb, chairman of the anesthesiology department at the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California, was critical of the second dosage given to Diaz. He said he has never made any statements for or against the death penalty.

"If an IV has to be given a second time, it is an indication it has not done right the first time," Lumb said.

An attorney representing Diaz's family, D. Todd Doss, said legal action was being considered.

"We are still grieving. It continues to get worse and worse, learning the details of what happened," said Sol Otero, Diaz' niece from Orlando. "The excruciating pain and torture my uncle went through for 34 minutes. He was literally crucified."

Associated Press writers Adrian Sainz and Laura Wides-Munoz in Miami contributed to this report.

|

By AUSTIN SARAT Monday, Dec. 18, 2006 By AUSTIN SARAT Monday, Dec. 18, 2006

Last Wednesday, the name of Angel Diaz was added to a long list of persons whose executions have been botched in recent American history. As widely reported in the press, it took Florida thirty-four minutes to kill him, twice the usual time. The needles that carried the lethal chemicals were mistakenly inserted completely through their intended targets--the veins in Diaz's arm--into the flesh of his arms. Thus, instead of being unconscious within the usual three or four minutes after the administration of the first chemical in the execution protocol, Diaz "appeared to be moving twenty-four minutes after the first injection, grimacing, blinking, licking his lips, blowing and appearing to mouth words."

After this execution, a spokesman for the National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty noted that "Florida has certainly deservedly earned a reputation for being a state that conducts botched executions, whether electrocution or lethal injection."

Like the king and his men trying to put Humpty-Dumpty back together again, Florida Governor Jeb Bush immediately reacted to the Diaz fiasco by reaffirming his belief in capital punishment, ordering a halt to all executions, and convening a special commission to review that state's lethal injection procedures to insure that, in the future, they do not result in cruelty and needless suffering.

Yet whatever Governor Bush's commission recommends, it is getting harder and harder for supporters of the death penalty to defend the system. The Diaz case is just the latest is a series of developments adding impetus to abolitionists' efforts to shift attention away from abstract philosophical debates, to the way the death penalty actually works.

Abolitionists have recent cited not only botched executions, but also dramatic exonerations of persons from death row, cases in which defense lawyers fell asleep during capital trials, and concerns over racial disparities in the death penalty system. These abolitionist arguments, each powerful in its own right, have gained so much traction that it now seems safe to say that the future of capital punishment in the United States is very much in doubt. Indeed, the prospect of its end, which once seemed so remote, is a distinct possibility in the foreseeable future.

Willie Francis's Progeny: The Most Famous Botched Execution in U.S. History

Perhaps the most famous botched execution occurred in the case of Willie Francis in the 1940s. In his case, the United States Supreme Court allowed the state of Louisiana to electrocute a convicted murderer twice.

As the Court recounted the relevant facts, "Francis was prepared for execution and on May 3, 1946...was placed in the official electric chair of the State of Louisiana...The executioner threw the switch but, presumably because of some mechanical difficulty, death did not result." Evidence was offered to suggest that during this botched execution Francis had experienced extreme pain, that his "lips puffed out and he groaned and jumped so that the chair came off the floor."

Sometime later, Francis sought to prevent a "second" execution by contending that it would constitute cruel and unusual punishment. Yet Justice Reed, writing for a majority of the Court, held that the first, unsuccessful execution would not "add an element of cruelty to a subsequent execution."

The constitutional question, as Reed saw it, turned instead on the behavior of those in charge of Francis's "first" execution. From the facts as he understood them, Reed found those officials to have carried out their duties in a "careful and humane manner" with "no suggestion of malevolence" and no "purpose to inflict unnecessary pain." He described diligent, indeed even compassionate, executioners whom he believed were frustrated by what he labeled an "unforeseeable accident...for which no man is to blame," and concluded that the state should not be deprived of a second chance to execute Francis.

The list of botched executions from Francis to Diaz is lengthy, and includes almost every imaginable kind of failure. Recently cataloged by sociologist Michael Radelet, that list includes Alabama's 1983 execution of John Evans. During Evans's electrocution, the electrode attached to his leg burst from the strap holding it in place, and caught on fire. Smoke and sparks also came out from under the hood over Evans's head, in the vicinity of his left temple. Two physicians entered the chamber and found a heartbeat. The electrode was reattached to Evans's leg, and another jolt of electricity was applied. This resulted in more smoke and burning flesh. Again, the doctors found a heartbeat. A third jolt of electricity was applied. The execution took fourteen minutes and left Evans's body charred and smoldering.

In 1997, newspapers around the country described the gruesome circumstances of the Florida electrocution of Pedro Medina. During his execution, a crown of foot-high flames shot from the headpiece, filling the execution chamber with a stench of thick smoke and causing the two dozen official witnesses to gag. An official then threw a switch to manually cut off the power and prematurely end the two-minute cycle of 2,000 volts. Medina's chest continued to heave until the flames stopped and death came.

After Medina's execution, prison officials blamed the fire on a corroded copper screen in the headpiece of the electric chair, but two experts hired by the governor later concluded that the fire was caused by the improper application of a sponge (designed to conduct electricity) to Medina's head.

As the Diaz execution reminds us, the problem of botched executions was not eliminated by the dramatic shift from electrocution to lethal injection; far from it. Radelet catalogs many instances in which lethal injection has misfired. To note but one example, in 1988, Raymond Landry was pronounced dead forty minutes after being strapped to the execution gurney, and twenty-four minutes after the drugs first started flowing into his arms. Two minutes after the drugs were administered, the syringe came out of Landry's vein, spraying the deadly chemicals across the room toward witnesses. The curtain separating the witnesses from the inmate was then closed for fourteen minutes, while the execution team reinserted the catheter into the vein. Witnesses reported "at least one groan." A spokesman for the Texas Department of Correction said, "There was something of a delay in the execution because of what officials called a 'blowout.' The syringe came out of the vein, and the warden ordered the (execution) team to reinsert the catheter into the vein."

These cases strongly belie the claim made by Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia in the 1994 case of Callins v. Collins that lethal injection is merely "a quiet death." In that case, Justice Harry Blackmun famously announced that he no longer would "tinker with the machinery of death," and would, as a result, vote against the death penalty in all subsequent cases. Scalia responded that while Blackmun had described "with poignancy the death of a convicted murderer by lethal injection," that death should be compared with what the murderer himself had done -- killing "a man [who was] ripped by a bullet suddenly and unexpectedly...[and] left to bleed to death on the floor of a tavern." Compared to the tavern murder, Scalia remarked, death by lethal injection was "pretty desirable." How enviable, Scalia continued, is "a quiet death by lethal injection compared with that!"

Reconsidering Lethal Injection; Examples Underline Its Cruelty

More than thirty states use the same three-drug sequence that Florida uses for lethal injections - the sequence that led to such horrific consequences in the Diaz case. In recent years, groups opposed to the death penalty have had increasing success arguing that the pain the cocktail inflicts constitutes "cruel and unusual punishment."

Indeed, two days after Diaz was put to death, Judge Jeremy Fogel of the United States District Court for the Northern District of California found that California's execution protocol and procedures were constitutionally defective, lacking "both reliability and transparency." As he put it, "California's lethal-injection protocol--as actually administered in practice--create[s] an undue and unnecessary risk that an inmate will suffer pain so extreme that it offends the Eighth Amendment."

Judge Fogel cataloged a long list of problems with the protocol, as it is applied in practice, including: inconsistent and inadequate screening of execution team members; a lack of meaningful training and oversight of the execution team; inconsistent and unreliable record keeping, such that in several cases it is impossible to even tell whether the execution protocol was followed; and improper mixing, preparation and administration of one of the drugs used in lethal injection.

Earlier this year, in a controversial ruling, the U.S. Supreme Court allowed another Florida death-row inmate to challenge that state's lethal-injection procedures through a federal civil rights lawsuit. Other states are now examining the method of execution long hailed as the most humane way of killing. In Maryland and North Carolina, federal judges have raised questions about the constitutionality of lethal injection and the procedures used to administer it. Missouri and South Dakota have delayed executions while lethal injection is reviewed, and Oklahoma has altered its procedure so that the prisoner receives more anesthesia before being executed.

Reconsidering the Death Penalty Itself: Are We Moving Toward Abolition?

In April 2005, Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney filed a long-awaited bill to reinstate the death penalty in his state. The bill, which Romney called ''a model for the nation" and the ''gold standard" for capital punishment legislation, limited death eligibility to a narrow set of crimes including deadly acts of terrorism, killing sprees, murders involving torture, and the killing of law enforcement authorities. It excluded entire categories of crimes that many believe also warrant the death penalty, including the murders of children, and the rape-murders of women. It also laid out a set of hurdles for meting out capital punishment sentences, in an effort to neutralize the kind of problems that have led to dozens of death-row exonerations across the nation in recent years. The measure called for verifiable scientific evidence, such as DNA, to be required before a defendant can be sentenced to death, and a tougher standard of ''no doubt" of guilt (rather than the typical "guilty beyond a reasonable doubt" standard) for juries to sentence defendants to death.

The narrowness and caution of Romney's bill were important signs that the tide has turned in the national conversation about capital punishment. Among the other signs of such a shift, three are particularly significant. First, in the realm of public opinion: support for life without parole, as an alternative to the death penalty, has steadily increased -- to the point where the country is now evenly split when asked whether they prefer the death penalty, or life without parole, as a punishment for murder.

Second, consider the dramatic decline in the number of people being sentenced to death in the United States. In 1998, 302 people were sentenced to death. In succeeding years, that number has steadily declined, to the point where, in 2005, it reached 125. Third, there has been a similar decline in the number of executions, from 98 in 1998 to 53 in 2006.

These facts all suggest that Americans have growing doubts about the need for capital punishment, as well as about the way it is administered. Botched executions add to those doubts, raising questions about whether it will ever be possible for the state to kill in a humane way.

These doubts and questions suggest that while abolition is not yet on the horizon, it may be not too far outside our field of vision. The botched execution of Angel Diaz probably will not be the last in the United States. Yet as history unfolds, what was done to Diaz may one day be seen as an important marker on the long road to the death penalty's demise.

Austin Sarat is William Nelson Cromwell Professor of Jurisprudence and Political Science at Amherst College. He is the author of When the State Kills: Capital Punishment and the American Condition (Princeton University Press) and Mercy on Trial: What It Means to Stop an Execution (Princeton University Press).

Archived from Find Law

|

|

Friday, December 15, 2006 - The Associated Press

The governor of Florida has stopped signing death warrants after the execution of a convicted killer in his state went awry and took twice as long as normal.

Angel Nieves Diaz's execution on Wednesday took 34 minutes ó twice as long as usualó because officials incorrectly inserted the needles that delivered the lethal chemicals, a medical examiner said Friday.

Gov. Jeb Bush responded to the findings by saying he won't sign any more death warrants until a commission he's created to examine the state's lethal injection process completes its final report by March 1.

Florida Gov. Jeb Bush has suspended executions in Florida.

(Michael Weimer/Associated Press)

|

Dr. William Hamilton, who is performing the autopsy, said the needles pierced Diaz's veins and then went into soft tissue in his arms. The lethal chemicals are supposed to go directly into the veins.

He said his findings are preliminary, as results from toxicology tests and other tests won't be ready for several weeks.

Hamilton refused to say whether he thought Diaz died a painful death.

"I am going to defer answers about pain and suffering until the autopsy is complete," he said.

Prisoner may have been moving 24 minutes into execution

Diaz appeared to be moving 24 minutes after the first injection, grimacing, blinking, licking his lips and blowing, an indication that the chemicals were going into tissues and not veins.

Executions in Florida normally take no more than about 15 minutes, with the inmate rendered unconscious and motionless within three to five minutes.

Diaz, 55, was put to death for murdering of the manager of a Miami topless bar during a holdup in 1979.

The condemned man not only took 34 minutes to die, but also needed a rare second dose of the lethal chemicals.

The medical examiner's findings contradicted the explanation given by prison officials, who said Diaz needed the second dose because liver disease caused him to metabolize the lethal drugs more slowly.

Hamilton said although there were records that Diaz had hepatitis, his liver appeared normal.

Bush said he's halting executions because he wants to ensure they don't constitute cruel and unusual punishment, as death penalty foes argued bitterly after Wednesday's execution.

David Elliot, spokesman for the U.S. National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty, said experts his group had contacted suspected that liver disease was not the explanation for the problem.

"Florida has certainly deservedly earned a reputation for being a state that conducts botched executions, whether it's electrocution or lethal injection," Elliot said.

"We just think the Florida death penalty system is broken from start to finish."

© The Canadian Press, 2006

|

By AUSTIN SARAT Monday, Dec. 18, 2006

By AUSTIN SARAT Monday, Dec. 18, 2006